Store windows.

It all started with store windows.

Shopkeepers rely on their windows to attract passerby customers and draw them

inside where they might make a sale. However in the early 1920’s, pens were

made with hard rubber, commonly called ebonite, and this material had some problems.

Ebonite, invented by Charles Goodyear in 1839, is made of naturally occurring

rubber mixed with sulphur and then heated or “vulcanized” The problem

is the sulphur. Not all of the sulphur bonds during the process and as much as

40% is left “free”. Ultraviolet light will force the sulphur to combine

with oxygen and this causes the discoloring. Also hydrogen and oxygen like to

bond with sulphur. Thus if ebonite is exposed to water, either in the air as humidity

or in liquid form, the surface will create a film of sulphuric acid on the pen

which burns the pen and also discolors the surface.

|

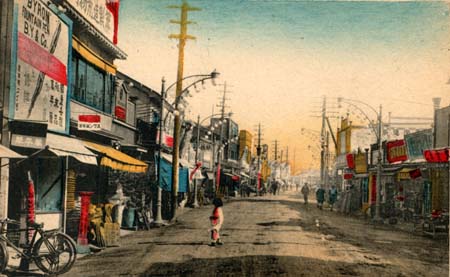

Pen shop in Yokohama 1917

1 |

A Japanese window is the worst place in the world for a hard rubber pen. The

air is hot and steamy in the summer, and the sun is always strong. A pen would

generally last a week before it discolored to a point where it would need to be

replaced. When the Pilot Salesman visited shops, trying to push more pens, they

were constantly met with the same complaints. The shop owners were irritated at

the number of pens wasted by displaying them in the windows and having to replace

them as they discolored. They often used Dummy pens, pens made of wood and painted

black to resemble the real pens, but these dummies were not as glossy as the real

pens and sales would decrease.

Pilot was well aware of the problem and they had been working on a solution.

For years they had been trying to perfect the vulcanization process. They tried

using more heat and pressure to minimize the free sulphur, but nothing seemed

to work.

In 1923 someone in the company had the idea to coat the pens with urushi lacquer.

In the Tokyo Museum there were several pieces of ancient silver artwork that had

been coated with this lacquer, and even after 800 years the silver hadn’t

tarnished. If the lacquer worked for silver why not hard rubber?

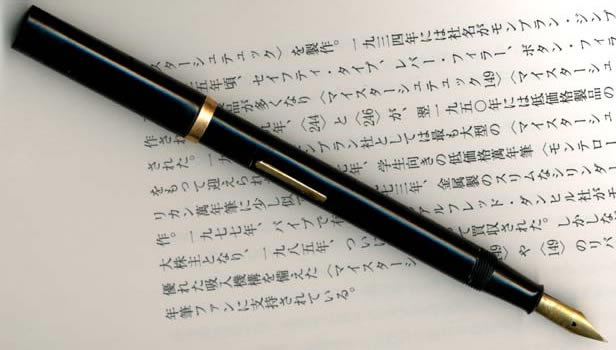

Pilot pen - 1923 lever filling Pilot

pre-Laconite lacquer 2

The Pilot engineers quickly discovered that urushi lacquer was

not easy to work. This lacquer comes from a tree that is closely related to poison

ivy. The factory workers tried spraying and dipping techniques to coat the pens

in mass production. This was a bad idea. They couldn’t get an even coat

on the pens, and the poor workers were covered in rashes and swollen eyes. Some

men were in such bad condition that they needed to be hospitalized. But the process

seemed to work. The pens had an uneven surface and some shopkeepers complained

about that, but after a week in the sun the pens still retained their luster.

Pilot lost no time marketing these pens. They promised the shopkeepers that

the pens would never discolor even if left in the sun, Guaranteed. This was unfortunate.

The lacquer delayed the discoloration, but after a few months the pens would discolor

just as before, and the shopkeepers demanded their money back. Pilot lost a lot

of money on these pens. Today these 1923 Pilots are very hard to find and are

very valuable to collectors.

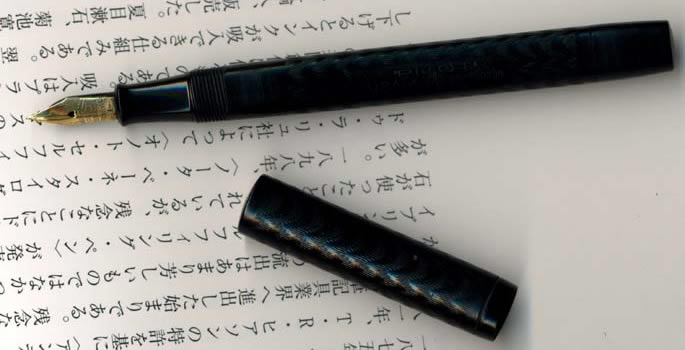

Pilot pen – 1926 Laconite finish

3

By 1925, after having rebuilt from the 1923 earthquake, Pilot finally solved

the problem and sought to reap untold profits. The solution was to take the hard

rubber stock and rotate it on a lathe at high speeds. Felt strips, saturated in

urushi lacquer were pressed against the stock. The friction heated the stock and

forced the lacquer deeper into the rubber’s pores, impregnating the stock

with the lacquer and the resulting material turned out better than expected. Even

after several months in the sun the pens did not lose their color. Pilot named

the new material Laconite and secured patent in Japan, the U.S. and England. Pilot

thought that the world would come rushing to them, wanting to license their invention.

They were a little too late as other companies were starting to look at new celluloid

and other plastic materials that were more colorful and easier to work.

Pilot pen U.S. patent imprint for Laconite

process 4

One company to take Laconite seriously was General Electric. The new material

had an interesting characteristic: Laconite was a far better insulator than plain

hard rubber, and GE licensed this for several years for telegraph insulators.

Disappointed, Pilot looked at their lacquer pens and went a step further.

They noted that their pens looked like all the other pens in the world, why should

anyone in a foreign market notice them? Fortunately someone asked, “Why

not use colored lacquer and traditional Japanese artwork?” The art of Maki-e

had been around for centuries. It seemed like an obvious decision to apply the

Maki-e artwork to pens. Sure, Pilot wouldn’t be able to mass produce pens

this way, but some customers would pay more for the artwork. It was this simple

idea that quickly launched Pilot as a major pen company. Many foreign companies

wanted to hire Pilot’s artists to make Maki-e pens for them, but Pilot refused,

they would not relinquish the name Namiki from their pens.

Eventually Alfred Dunhill would compromise and use both the Namiki and Dunhill

names on the pens for the exclusive rights to sell the pens abroad. The rest is

history.

- This is a postcard showing a street

in Yokohama. In the image you can see a shop named Byron Fountain Pens. You would

think from the name that this would be a Foreign Shop, but it is surely owned

and run by the Japanese. During this time, foreign products were considered far

superior so shopkeepers nearly always chose a foreign name. The postmark dated

the card to 1917. This is a year before Pilot began selling pens, but in the signs

advertise Swan Pens (this would be the Japanese maker not Mabie Todd) and Sanesu

(or SSS, the name means three S's) The top sign advertises Japanese Pens, Import

Pens and repairs. In any case it is interesting to see what small local Japanese

pen shops looked liked back then. The Large Department stores in Tokyo were more

modern for the time and was where most of the selling took place.

- This is a 1923 Lever-filling Pilot

pre-Laconite lacquer pen. These early lever fillers are exceedingly rare. It was

too expensive if at all possible to replace the rubber sacs, which often rotted

or turned to goo in Tokyo's tropical summers and the ultra-humid rainy season.

- Illustrated is a 1926 Laconite pen.

Pilot sold over 400,000 of these pens in 1926, more than twice as many as they

had sold from the years between 1918-1925. It was just the break Pilot needed

as they were trying to repay their creditors. It was also the first time Pilot

was seen as a quality pen maker. Before 1926, Swan and San-essu were seen as the

leaders.

- The imprint gives the US patent number

for the Laconite process.

Ron

Dutcher has lived in Japan for over 15 years, where he owns and runs a small orthopedic

clinic with his wife, Keiko; which leads him to many Japanese pen finds. His patients,

once they learn of his pen hobby often give him pens as gifts or offer to sell

them to him. He is a member of the Tokyo Pen Association, and has learned a great

deal from Japanese pen collectors. He sells a great many Japanese pens on ebay

under the name Kamakura-Pens, but his true love is for early American pens. He

can be contacted at rd@kamakurapens.com Ron

Dutcher has lived in Japan for over 15 years, where he owns and runs a small orthopedic

clinic with his wife, Keiko; which leads him to many Japanese pen finds. His patients,

once they learn of his pen hobby often give him pens as gifts or offer to sell

them to him. He is a member of the Tokyo Pen Association, and has learned a great

deal from Japanese pen collectors. He sells a great many Japanese pens on ebay

under the name Kamakura-Pens, but his true love is for early American pens. He

can be contacted at rd@kamakurapens.com

|