|

I had just returned to my home in

Tokyo after a long vacation when I discovered

a week-old e-mail FROM Toshiya Nakata,

president of Nakaya Fountain Pen Company,

asking me to join him and colleagues Mrs. Noritsuke

and Mr. Suzuki of the Platinum Planning

Division on a trip the next day to Aizu

to meet maki-e artists, Hideaki

Sone and Katsuhiko Terui.

Natural and colored

urushi (in cups, covered with plastic wrap)

with brushes

|

These

were the same two craftsmen who came with Platinum

to demonstrate their art at the 2001 New York

Pen Show.

So early the next morning, I found myself back

on a bullet train speeding through the mountains

of Fukushima prefecture, camera in hand

(which I was requested to bring so I could write

up an article about the day's events).

I was a bit surprised when I was asked to pay

for my own train ticket--roughly $142.00 round

trip--but I took this as an indication of the

financial health of this, and probably a lot of

other Japanese fountain pen companies, in this

era of ballpoints and rollerballs.

After an hour and a half on the bullet train,

and another hour on a local line, we arrived at

Aizu-Wakamatsu station where Mr. Sone was

waiting for us with his car.

Aizu-Wakamatsu is quiet and peaceful town is

famous for its long history as a center for urushi

lacquerware.

Urushi is a natural sap taken FROM

the urushi tree, and is very expensive.

Its natural color varies FROM a light brown to

almost black. It will also cause skin poisoning

if you touch it--unless you have been working

with it so long that you've built up an immunity.

The process of coating a wooden object with

urushi takes many steps, and the process

varies according to the shape of the object. Bowls

take one process called marumo while

boxes with flat surfaces take a different

process called itamo. The basic

procedure for both of these share the following

steps:

- Apply

a foundation layer of urushi with a brush

to cover the wood grain. This step is called

kitagame.

- Apply

another layer of paste made of clay powder and

urushi. This step is called shitaji.

- Sand

the entire surface and apply another coat of

urushi.

- Sand

the entire surface again and apply another coating

of urushi. This step is called nakanuri.

- Lightly

sand again and apply a final coat of urushi.

This step is called uwa nuri.

(Between each of these steps is a drying period

of several days.)

As

you can imagine with all the sanding and coating,

the final product is very shiny and smooth doesn't

even look like wood anymore. The color is usually

a deep black or warm red. The art of urushi

has been around since the Jomon period, ca.

12,000 B.C. - ca. 400 B.C. Back in an era

when plastic was unheard of, such objects must

have caused quite a stir.

Black

or red Urushi lacquerware can be further

decorated with Maki-e or some other

process. Maki-e involves sprinkling gold

or silver or colored powders onto

the wet urushi. The maki

in maki-e is the same Japanese word used

for "sowing" seeds. The "e" (short

vowel) means "picture." So maki-e

means "sprinkle pictures."

Other

decorative styles include urushi-e

which is painting images directly with a brush

and colored urushi (mixture of colored

powder and urushi), and chinkin

which involves carving images INTO the surface

of the wood and then coloring the grooves with

gold foil.

In

recent times, the number of maki-e craftsmen

has dwindled, and the process itself has evolved.

Eighty percent of the work these days is done

by silk screen rather than by hand painting.

Hideaki Sone

|

First

we went to Mr. Sone's home where he showed us several

beautiful treasures including a stunning box completely

covered with gold, and decorated with flower images,

and which was not for sale at any price. It had

taken him and his father six months to complete.

Terui and son

|

Both Mr.

Sone and Mr. Terui learned the trade

FROM their fathers who were the first

two maki-e artists to be officially recognized

by the Japanese government. Mr. Terui has passed

the trade onto his son, Katsuhiro, while

Mr. Sone has apprentices FROM outside the family.

We asked Mr. Sone what qualities make a good apprentice,

and he simply replied, "perseverence."

Mr. Sone then took us to meet Mr. Terui and

his son, and the whole GROUP headed for a locally

famous soba restaurant where we talked about the

local community, their craft, pens, and their

trip to the New York Pen SHOW last year.

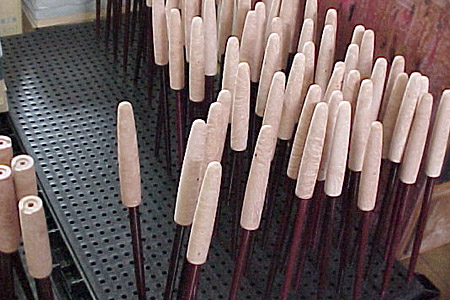

After lunch, we went to Mr. Sone's studio, where

there were rows and rows of pen barrels and caps

mounted on chopsticks. There were briar, plastic,

and black hard rubber pens. While traditional

urushi and maki-e has always been

applied to wood, maki-e pens have expanded

to include these other materials, even brass.

Pen barrels made of

briar

|

Hand-painted pine bough

maki-e pen

|

Mr. Sone

sat down and demonstrated for us his method of hand

painting a pine bough maki-e decoration

on a pen. First he painted the pine needle portion

with yellow colored urushi. Then, while it

was still wet, we sprinkled green powder on it and

dusted off the excess. He painted a few pen barrels

this way and set them aside to dry. Later, he would

go back and paint the branches.

Next he demonstrated a maki-e technique

using fine strips of gold and abalone.

First he coated the barrel with urushi

which he stores in custom made tubes. This urushi

was a dark brown like molasses and had a natural

and rather unpleasant smell. Next, he carefully

pressed the strips of gold and abalone (which

he had cut earlier) one by one INTO the wet urushi.

Then, he loaded some fine powdered gold gold INTO

one end of a small hollow bamboo rod.

Fine

silk was stretched over the opening on the other

end. Then with delicate tapping, he began to sprinkle

the gold dust over the still-wet urushi.

Before he began this stage, he had us close the

door and windows to prevent the wind FROM causing

a disaster.

Finally

he placed the pen barrel in a cabinet on a vertical

wheel which automatically revolves periodically

to allow even drying without the unwanted effects

of gravity. Later he would coat the entire barrel

with dark urushi and then apply a technique

called togidashi to once again let

the abalone and gold shine through. This technique

is further explained below.

After

asking a few more questions of Mr. Sone and discussing

current projects, and plans for a new line of

Nakaya maki-e pens, we went to visit the

home of Mr. Terui. He and his family live in a

big traditional Japanese home, but with the loft

converted INTO a studio. There was quite a display

of maki-e and other urushi treasures

including wall sized panels covered with intricate

designs. There were also rows of drying maki-e

pens.

Mr. Terui demonstrates togidashi |

Mr. Terui

and his son explained the technique of taka-maki-e

which is characterized by raised images on

a black urushi background. First, the image

is painted onto a dried surface of urushi.

After this image has dried, another coating of urushi

is applied over the entire surface, including the

image, which becomes almost obscured by the dark

color of the urushi. Once this coat has dried,

the image is rubbed over with soft wet charcoal

until it starts to SHOW through again. This process

is called togidashi. It is repeated

several times, with the gradual building up of the

painted image in several layers (with more details

added each time), alternating with further coating

and stripping urushi. The result is beautiful,

sharp contrast--which you can both see and feel--between

the raised painted images and the deep urushi

background, like bright objects emerging FROM a

dark pool.

After a bit of discussion of business matters

(concerning current and future pen projects),

we left the Terui household for the station to

catch an evening train back to Tokyo.

I

personally took back with me a new appreciation

and sense of awe regarding this ancient Japanese

art which has only been applied to pens in recent

years. I now regard the one hand-painted maki-e

pen I own as a true treasure with which I will

never part. |