| [Note: This is by no means meant to be a complete history of the Pelikan

pen or the Günther Wagner firm. Readers seeking the fullest account of Pelikan

should consult Jürgen Dittmer and Martin Lehmann’s Pelikan Schreibgeräte.

A list of sources and additional reading is to be found at the end of this piece.

Rather this is meant to be a readable introduction to Pelikans for beginning collectors

and newcomers]

The history of Pelikan begins with Germany’s industrial revolution in

the early nineteenth century and continues into the global economy of today. During

that period, the firm has consistently been a technological leader, even as it's

fortunes rose and fell. In 1863 Günther Wagner became partner in a business

founded by Carl Hornemann of Hannover, a member of the newly empowered German

parliament. Since 1838, the firm had been producing artist’s supplies using

the newly developed technology of chemical dyes, a field in which Germany led

the world. Eight years later Wagner took over the business giving it his name

and expanding it into office supplies. In 1878, Wagner added the name of Pelikan,

from one of the elements in his family crest. Following Wagner’s retirement,

a decade later, his son-in-law and successor, Fritz Beindorff led the company

to become one of the world’s leading makers of fountain pens.

Although Wagner was late to enter the field, they revolutionized the manufacture

of German fountain pens with the first piston filler. Today, collectors from around

the world put huge amounts of money, time, and energy into collecting what began

as a homely little expression of German modernist pen design.

1st year pen—From the collection

of Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas. Jade 1929 pen.

The first Pelikan fountain pen was introduced in 1929 and was something different

in the world of pens. It had to be, for the firm had come to the market late but

with a remarkable innovation in filling systems.

Compared to most fountain pens of the 1920s, the original eyedropper-filler

had been highly efficient with only two moving parts and a large capacity. But

it was messy, cumbersome and time consuming. As early as 1905 Evelyn Andros de

la Rue developed a piston filler but, according to Andreas Lambrou, it was a cumbersome

device that did not catch on beyond the firm’s own products. By the mid

1910s, the sac and the various devices used to compress it had become the dominant

filling system in England and America. But sacs took up space and required an

actuating mechanism, be it a lever and pressure bar, a crescent, a button or any

of dozens of other attempts to devise an elegant and effective filler. In Germany

and throughout the continent, a variant of the eyedropper, the so-called safety

pen, dominated.

So, by the late 1920s penmakers were ready to go beyond the eyedropper and

the sac, but where? This was an age of innovation, so on various fronts in Europe

and the United States the search was on for a system that would let the barrel

itself contain the ink with some device to fill it. The rod and seal was one approach,

taken by Omas, Onoto and Sheaffer, the diaphragm was another, used most successfully

by Parker and by Waterman and Osmia.

Then came the piston. An eastern European engineer, Theodor Kovacs appears

to have been the first to devise the modern piston filler and secured a patent

for it, probably in 1925. Kovacs’ design used a shaft mounted with a cork

seal as a piston and a telescoping device attached to a turning knob to advance

and retract it.

Exploded view - image courtesy of Pelikan

In order to produce a pen based on his innovation, he went into partnership

with two brothers, Edmund and Mavro Moster, who controlled the Croatian firm Penkala.

By 1927, however, the Mosters were in financial difficulties and Kovacs sold his

patent to Günther Wagner. Two years later the first Pelikan was produced

and within five years of its release the telescoping piston filler revolutionized

European pen manufacture, replacing the favored safety filler. Before long, even

the giant, Montblanc, was forced to adopt the piston filler, touching off a generation

of close and often litigious rivalry between the two firms.

Initially, however, their relationship was much more cooperative. Beginning

in 1924, Montblanc relied on Pelikan for ink, and Pelikan, which did not have

its own metal working facilities before 1935, relied on Montblanc for nibs. How

long that relationship lasted, whether for only the first year, or until the mid-1930s

is not clear. Today, the early Pelikan nibs, whoever made them, are most highly

prized by collectors. Those nibs, especially the flexible obliques, define the

Pelikan pen. (We’ll have more on Pelikan nibs in a few weeks.)

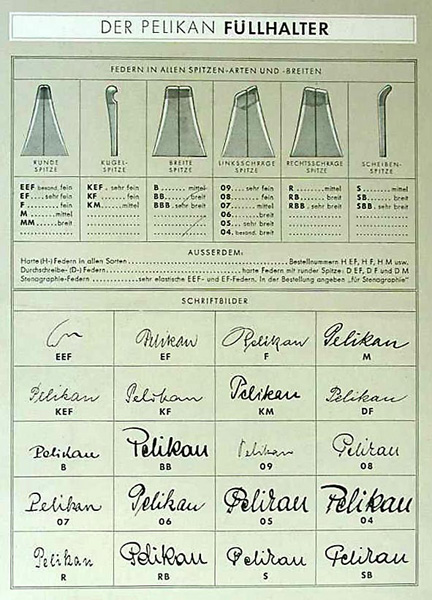

from the collection of Gerhard Brandl/photography

by Gerhard Brandl. The classic Pelikan nib chart.

Despite the economic woes of Germany, which were only heightened by the worldwide

Depression that hit the United States in 1929 and Europe the next year, Pelikan

prospered. The firm’s success came for a number of reasons. Foremost, was

the firm’s worldwide reputation as a respected maker of artist supplies

and office products for more than fifty years. Related to this was the firm’s

ability to aggressively market and promote the pens. Finally, there was the product

itself.

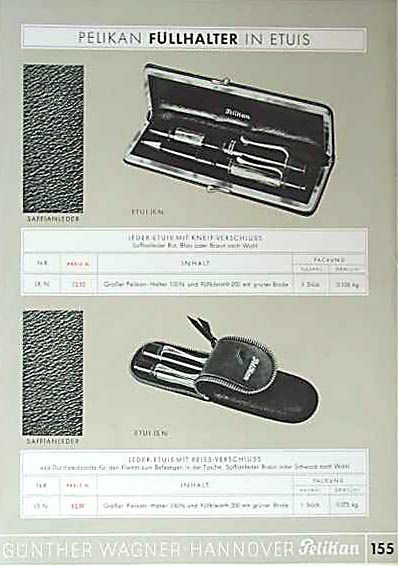

from the collection of Gerhard Brandl/photography

by Gerhard Brandl. Circa 1938.

from the collection of Gerhard Brandl/photography

by Gerhard Brandl. Circa 1938.

The Pelikan 100 was a model of simplicity from top to bottom, the epitome

of form following function. (The number 100, by the way was only adopted in 1931

to distinguish it from subsequent models.) The pen was also a superb example of

the German modernist style, which later spawned the more widely known Bauhaus

movement. Pelikan took advantage of this in their early advertising, stressing

the pen as a product of modern industrial design and illustrating the point with

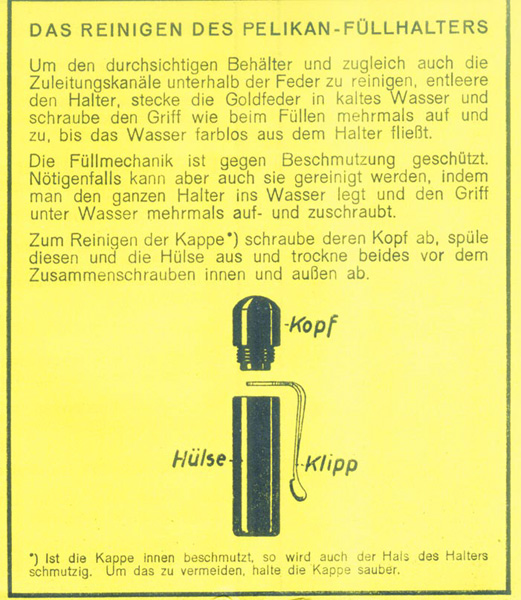

exploded diagrams. The high captop, designed primarily to serve as an inner cap,

screwed into the plain, unadorned cap tube (the first models had no cap rings),

and leaflets included with the early pens showed users how to disassemble the

cap to clean it.

The washer clip (or as Pelikan called it the drop clip) married form and function

perfectly. Easy to remove or replace if damaged, the sleek, distinctive style

modernistically evoked the shape of the bird’s beak, and represented Pelikan

to the world until after World War II when the clip came to more closely resemble

a pelican’s beak.

from the collection of Gerhard Brandl/photography

by Gerhard Brandl. A tray of Pelikans from 1929 and 1931

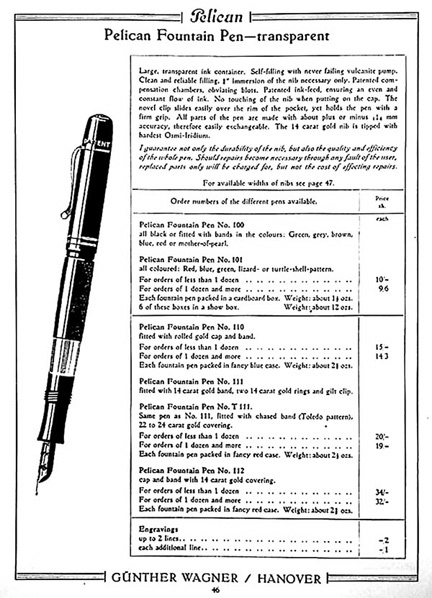

from the collection of Gerhard Brandl/photography

by Gerhard Brandl. English language catalog Circa 1934.

The rest of the pen, the body or shaft, made from bakelite, was a simple one

piece tube (this would change after the first year when they went to celluloid

and hard rubber construction) with the nib assembly at one end. At the other end

a three piece filler mechanism reverse threaded into the barrel. There was the

so-called cone which was a keeper for the filler itself consisting of a hollow

shaft and piston. The piston then telescoped into a solid shaft attached to the

knurled filler knob stamped with an arrow to indicate the direction to turn at

the other. That was it. The only decoration came with the distinctive barrel band

(in German, the Binde), to this day a feature of the top-line Pelikans.

100s—From the collection of Rick

Propas/photography by Rick Propas.

Tray

of early Pelikans in various colors, 1929-1934.

Initially, the pen came in two versions, first was the jade green, similar

to Sheaffer’s green) with the unadorned black hard rubber cap.

Photography by David Isaacson, pen from

the collection of Rick Propas. (1929)

That was followed by the traditional German black, with the celluloid Binde

and the plain black cap. According to legend, the conservative German business

class favored black pens

Photography by David Isaacson, pen from

the collection of Rick Propas. (1929)

because the earliest hard rubber pens had been of that color. Unlike Americans

who thronged toward the rainbow of colors first made possible by the advent of

celluloid in the mid-1920s, Germans had to be coaxed in that direction. Pelikan

did their best.

Among these early pens there seem to have been infinite variations of green,

but the early green bindes can be lumped into three types, the familiar marbled

green (marmoriert), the much less common early jade, which looks like the Sheaffer

green, and a variant of the marbled green made from cut strips of celluloid laminated

together.

Photography by David Isaacson, pen from

the collection of Rick Propas.

The question of variations in color is a more complex one. In many cases time

has faded and shifted colors, so that today we have all sorts of shades of green,

from near grey to olive to still brilliantly true colors, but as they were produced

the first pens were green, plain and simple.

Green 100s—From the collection

of Rick Propas/photography by Rick Propas.

and there was black. Pelikan hedged their bets against German conservatism.

Within a few years Pelikan also entered the market for low priced school pens

with first the Rap-pen and then the Ibis, later to be followed by the 120, 140

and Pelikano.

Note: Any history of Pelikan must rely on

two basic accounts, those of Jürgen Dittmer and Martin Lehmann in Pelikan

Schreibgeräte, and Andreas Lambrou, most completely in Fountain Pens of the

World. In addition, I have used Pelikan’s own company history, available

at ChartPak. I also

found helpful material in The PENnant (vol.XV, no.2, Summer 2001) which was devoted

to Pelikan and which I edited. Other material on pen history in general came from

Bowen and Lambrou. There is a small amount of useful Pelikan material in Miroslav

Tischler’s Penkala Writing Instruments. Regina Martini’s Pens &

Pencils, is a good source for identifying models and for background.

I am indebted to Gerhard Brandl, Jurgen Dittmer, Martin Lehmann,

Sharon Propas and Len Provisor who read, commented and fact-checked this history.

I, and not they, however, am responsible for all errors, omissions and bad commas.

Text © 2003 Rick Propas. Photos © 2003 as indicated in

captions.

|