|

Professor John Ronald Reuel Tolkien.

The author and scholar J.R.R. Tolkien holds a special place in

my life. How could it not be so, for I live on the borderland of fabulous and

fearful places which exist in another world, that of Middle Earth, the setting

of Tolkien’s most famous works of fiction, ‘The Hobbit’ and,

most notably, ‘The Lord of the Rings’.

The epic fantasy of ‘The Lord of the Rings’ in particular

took hold of me during my teenage schooldays, and I well remember spending a glorious

week in the summer of 1975 reading my way – no, questing my way –

through the entire trilogy. Books of that power do not disappear after you put

them back on that shelf, they become part of you, they change your world.

Yet it was not until many years later that I discovered that

my own home town, Bloxwich, itself more than 1,000 years old, was a part of that

area which apparently inspired Tolkien’s dark land of Mordor – ‘The

Black Country’. And one of my favourite haunts, the city of Birmingham,

England, contained within its suburbs and surroundings elements of The Shire,

Hobbiton, and The Two Towers. Imagine living within a few miles of Mount Doom,

or Barad Dur, or a short bus ride from the homes of Hobbits, or the lairs of great

wizards and the fortresses of warriors. Go back far enough in time, enter the

depths of your imagination, and some of it might even be true – after all,

Tolkien supposedly wrote these stories as a ‘mythology for England’,

and certainly they were loosely based on elements of the old Norse and Anglo-Saxon

legends.

Yet, how and when did Tolkien himself come to be inspired by

these places, you may ask? Simple enough – childhood memories, like mine,

inspired him. This series of three articles will tell you a little about the man,

the places that we know inspired him, and the shadows of what may have done. Let

us set out on our quest – on the trail of Tolkien – with a concise

biography and bibliography.

Part 1: JRR Tolkien: A boy, the man and his books

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born on 3rd January 1892 in Bloemfontein, South

Africa. His parents had both originated in Birmingham, England (once at the heart

of the Industrial Revolution, and now known as Britain’s ‘second city’).

They had emigrated in search of a better life. Sadly, it was not meant to be.

Three years later, Ronald’s mother, Mabel, returned to

England, taking him and his younger brother, Hilary, to Birmingham to visit their

grandparents for the first time. Whilst they were staying with her parents in

Kings Heath, Birmingham, Mabel received an unsettling letter revealing that her

husband had contracted rheumatic fever. Sadly, he died before she was able to

take the family back to South Africa.

Mabel Tolkien decided that there was now little reason to return

to their home in South Africa, and that they would instead settle in what was

then the rural hamlet of Sarehole, now a largely built-up residential area on

the border of the Moseley and Hall Green areas of Birmingham. Here, they lived

for four years at No. 264, Wake Green Road, which is a fine, attractive semi-detached

house of individual style, still in occupation as a private residence.

No. 264, Wake Green Road, Moseley,

Birmingham.

While the family lived in Sarehole, the boys explored wonderful

places such as Sarehole Mill (an 18th century water mill, still in operation as

a museum) and the wilds of Moseley Bog (now a nature reserve). Sarehole was later

to become the inspiration for The Shire, and Moseley Bog for the Old Forest and

Fangorn, and was the scene of the happiest days of Tolkien’s childhood.

The Old Mill at Hobbiton – Sarehole

Mill, Birmingham.

An Ent in the Old Forest (Moseley Bog,

Birmingham).

When it was time for Ronald to undertake serious schooling, the

Tolkien family moved to No. 214, Alcester Road, Moseley, from where they could

take a tram (streetcar) to King Edward’s School, Birmingham, making daily

transport much simpler. The school’s Victorian Gothic revival buildings

stood in New Street, in the city centre, not far from the exit ramp from the present

railway station. Sadly no longer in existence, the site is marked by a blue commemorative

plaque.

Before long the family moved again, this time to Westfield Road,

Kings Heath, and then to Ladywood, not far from the city centre. Mabel Tolkien

was a recent convert to the Catholic faith and had worshipped at St. Anne’s

Church, Alcester Street. Now she joined Cardinal Newman’s community at the

Oratory on the Hagley Road (still in existence today). The family moved into a

house in nearby Oliver Road and Ronald was enrolled briefly at St. Phillip’s

School in the same street.

The Oratory, Hagley Road, Birmingham

It was while living in the Ladywood area that Ronald discovered

what is apparently the inspiration for the Two Towers, commonly held to be ‘Minas

Morgul’ and ‘Minas Tirith’, the Two Towers of Gondor, though

there is some debate about this, as we shall discover in my next article. The

Two Towers, in real life, are an extraordinary 18th century tower called Perrott’s

Folly, and a later Victorian tower, in fact a huge, gloriously Italianate chimney,

at Edgbaston Waterworks. Both are preserved today, and may be seen from nearby,

although they are not normally open to the public. A further tower, the clock

tower of Birmingham University, may also have suggested Orthanc, the fortress

of the corrupted wizard Saruman, but more of that in part 2.

The Two Towers, Waterworks Road, Birmingham

Mabel Tolkien drew strength from the friendship of Father Francis

Xavier Morgan. However, her part of the Tolkien story was drawing to a close and,

diagnosed as a diabetic, she died in 1904 while convalescing, with the boys, at

the Oratory’s retreat near Rednal. Father Morgan remained a great source

of strength to the family during her illness and death, and became the boys’

guardian. Ronald was to remain a Catholic for the rest of his life.

Following their mother’s death, the boys remained in the

Ladywood area, but they were not happy staying with their aunt in Sterling Road,

and eventually moved to lodgings in Duchess Road. It was while living here that

Ronald met his future wife, Edith Bratt, who was aged 19, and he 16.. Father Morgan

attempted to put an end to the relationship by moving the boys once more, to their

last Birmingham address, No. 4, Highfield Road. Father Morgan forbade Ronald to

see or correspond with Edith until he was 21, and Ronald complied.

It was here that Ronald learned that he had gained a place at

Oxford University, and subsequently going up to Exeter College in 1911, he left

Birmingham for good, immersing himself in the Classics, Old English, the Germanic

languages (especially Gothic), Welsh and Finnish, but obtained a disappointing

second class degree, though he had done exceptionally well in philology. This

caused him to change his school from Classics to English Language and Literature.

In 1913 he felt able to renew his relationship with Edith, and

she converted to Catholicism and moved to Warwick, a place whose fine medieval

castle and wonderful countryside made a strong impression on Tolkien. In 1914

the Great War broke out. Ronald finally received his first class degree in 1915.

He eventually signed up as a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers, and

saw service on the Western Front and in the Somme offensive, but before he left,

he and Edith married in Warwick on 22nd March 1916. It was during his time at

the Front that he succumbed to ‘trench fever’ and as a result was

transferred home, spending a month in a Birmingham hospital. Most of his close

friends had been killed in the war, and his experiences in that great and desperate

conflict were to colour many similar aspects of his later writing of the fictional

early history of Middle Earth, and were to help form a basis for The Lord of the

Rings.

After the war ended in 1918, he was appointed Assistant Lexicographer

on the New English Dictionary or ‘Oxford English Dictionary’, and

in the summer of 1920 he applied for the post of Reader (roughly speaking, Associate

Professor) in English Language at the University of Leeds, and it was there that

he collaborated with E. V. Gordon on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and worked

on his invented "Elvish" languages.

By 1924, Ronald and Edith had three sons, and in 1925, the Rawlinson

and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford became available, and Tolkien

was appointed to the post. Before long, Professor Tolkien became involved with

an informal group of literary-minded friends with similar interests, known as

‘The Inklings’, who met at the Eagle & Child public house, and

including Owen Barfield, Charles Williams, and most significantly C. S. Lewis.

The Eagle and Child pub, on St. Giles,

Oxford, not far from the Ashmolean Museum.

Tolkien was to remain at Oxford for the rest of his life, teaching,

researching, and becoming a highly respected scholar. His phenomenally successful

career as a novelist came about almost by accident, when a story he had written

for his children, ‘The Hobbit’, was brought to the attention of publisher

Stanley Unwin by Susan Dagnall, an employee of the publishing firm of George Allen

and Unwin (merged in 1990 with HarperCollins). ‘The Hobbit’ was published

in 1937, and was a great success, becoming a perennial classic of children’s

literature.

The Radcliffe Camera, Oxford.

Tolkien

once remarked that this building resembles Sauron's temple to Morgoth on Numenor.

But it was to be sixteen long years before Tolkien’s ‘magnum

opus’, ‘The Lord of the Rings’ was completed, having developed

out of The Hobbit and many other writings which at the time were not seen as commercially

viable. Thanks to Rayner Unwin, son of Stanley, the company persevered with their

sometimes temperamental author through these many years, and in 1954 the first

volume, ‘The Fellowship of the Ring’ was published, with the final

two, ‘The Two Towers’ and ‘The Return of the King’ following

in 1954 and 1955. What at first seemed an unlikely success in effect created its

own market for literary high fantasy, and during the 1950’s and especially

the 1960’s became a cult success, especially when the books were pirated

in the United States. The rest, as they say, is history.

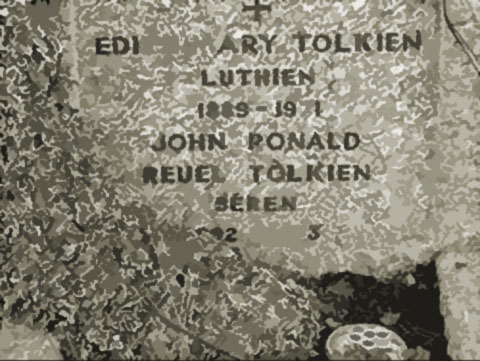

Following his retirement in 1969 Edith and Ronald moved to Bournemouth,

on the south coast of England. After Edith died in 1971, Ronald returned to Oxford,

where he died on 2nd September 1973. He and his wife are buried together in a

single grave in Wolvercote cemetery, Oxford.

A last resting place

EDITH MARY TOLKIEN LUTHIEN 1889-1971 JOHN RONALD REUEL TOLKIEN BEREN 1892-1973

There is no room here to look into the remarkable quantity of

both published and unpublished work that forms J.R.R. Tolkien’s staggering

literary legacy, much of which was published, often incomplete, in the years following

his death, and even more of which is commentary on his work by others. Tolkien’s

astonishing influence on the development of what today is known as ‘fantasy’

fiction is clear and undisputed, however, inspiring much that is good and also

much that is complete rubbish, and spawning the derogatory term which often describes

poor quality derivative fantasy as ‘sub-Tolkien’!

Although he was the author of important works on Anglo-Saxon

language and Middle English, including a recently discovered manuscript translation

of ‘Beowulf’, it is for his fantasy novels that J.R.R. Tolkien will

always be best known, and best loved, and in 2000 The Lord of the Rings was voted,

in a British survey, the ‘Book of the Century’. Now, an astonishingly

successful series of movies of ‘The Lord of the Rings’, by Peter Jackson,

have brought Tolkien’s work, albeit in modified form, to an enthusiastic

new audience, which in turn is returning to the books in droves. It is testament

to Tolkien’s towering imagination that it took nearly 50 years for the movie

industry to catch up with his world of elves, dwarves, hobbits, orcs and wizards,

and to do his books justice at last.

Next year is the 50th anniversary of the publication of ‘The

Lord of the Rings’, and no doubt the celebrations will echo around the globe.

The legacy of the little boy who spent his youth in Birmingham, as with the road

which Bilbo and Frodo both took, “goes ever on and on”. In my next

article, we shall visit the place where it began.

J.R.R. Tolkien: A Concise Bibliography

The Bodleian Library, Oxford

In order to keep this listing manageable for the purposes of

this article, only first editions of books published within Tolkien’s lifetime

are shown below. Those wishing a more complete listing of works which were reworked

and rediscovered and published after Tolkien’s death, including later editions

and American editions, would be well advised to read the excellent bibliographies

at:

The Tolkien Society website: http://www.tolkiensociety.org/tolkien/bibl2.html

The Tolkien Books Page by Jesse Chuhta: http://www.mines.edu/stu_archive/jchuhta/tolkien.html

The latter in particular offers listings of a great many books about Tolkien as

well as those by him!

‘A Middle English Vocabulary’. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1922.

‘Sir Gawain & The Green Knight’. Ed. J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon.

The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1925

‘Songs for the Philologists’. Privately printed in the Department

of English, University College, London, 1936.

‘The Hobbit: or There and Back Again’. George Allen and Unwin, London,

1937.

‘The Reeve's Tale’. Ed. "J.R.R.T." Oxford, 1939.

‘Sir Orfeo’. The Academic Copying Office, Oxford, 1944. Ed. by Tolkien.

‘Farmer Giles of Ham’. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1949.

‘The Fellowship of the Ring: being the first part of The Lord of the Rings’.

George Allen and Unwin, London, 1954.

‘The Two Towers: being the second part of The Lord of the Rings’.

George Allen and Unwin, London, 1954.

‘The Return of the King’: being the third part of The Lord of the

Rings . George Allen and Unwin, London, 1955.

‘The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book’.

George Allen and Unwin, London, 1962.

‘Ancrene Wisse: The English Text of the Ancrene Riwle’. Early English

Text Society, Original Series No. 249. Oxford University Press, London, 1962.

‘Tree and Leaf’. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1964.

‘The Tolkien Reader’. Ballantine, New York, 1966.

‘Smith of Wootton Major’. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1967.

‘The Road Goes Ever On: A Song Cycle’. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1967.

|